The Beauty of Kinbaku

Chapter Four

John Willie and Kinbaku

(… or what did one of the most famous early

Western bondage artists learn from the Japanese?)

by Master "K"

One of the most interesting aspects of researching “The Beauty of Kinbaku” was the differences I found between Western style rope “bondage” and Japanese erotic Kinbaku. For instance, it has been said by minds wiser than mine that while “Western ‘bondage’ is a method of restraint, often based on a point to point technique, Kinbaku is an aesthetic of restraint with hundreds of years of history, art and practice.” Still, that isn’t to say that we in the West don’t have attractive styles of tying when applied to a willing partner. And we even have a history of sorts for this, however brief it might be.

Or everything you always wanted to know about Japanese erotic bondage when you suddenly realized that you didn't speak Japanese

Kinbaku

and Art

Please note: no part of these articles may be reproduced by any means without the express written consent of the author or the publisher, King Cat Ink.

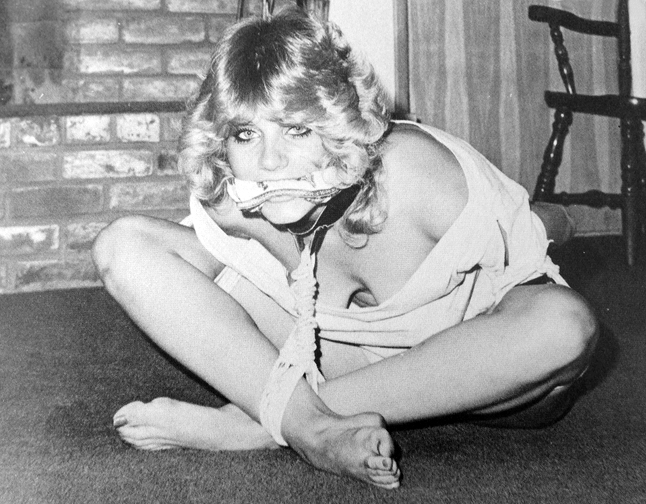

Western bondage, US Men's magazine illustration, circa the 1970's-1980's.

This page is best viewed on Google Chrome.

Two interesting related questions about Western bondage are, when did any sorts of art or methodology in erotic tying begin in the West and who was responsible for them? After all, to most eyes, Western bondage is much simpler in many respects than the more complex Japanese style of tying.

Partially this is due to the fact that we in the West progressed pretty quickly from rope to metal restraints. This left only such professions as cattle rancher and sailor, to say nothing of the venerable Boy Scout, to use rope in creative ways. By contrast, as I explain in my book, in Japan rope has always been an important part of culture, religion and society and so it was natural that they would stick with it through the ages as a means of erotic restraint. This is why the “art” of erotic rope bondage there grew in sophistication and complexity over time.

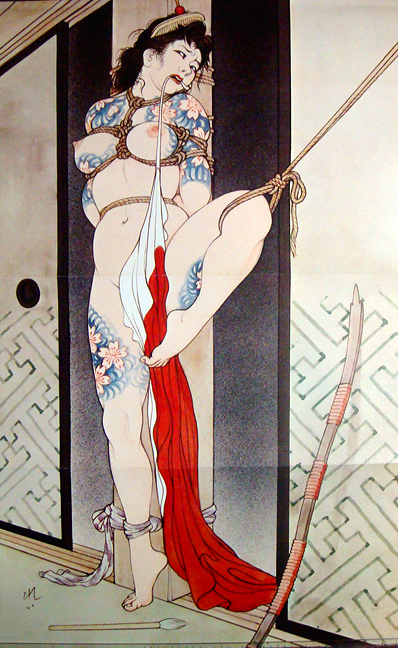

A beautiful illustration from master Japanese Kinbaku artist Kita Reiko, circa 1975.

To answer the question of when Western bondage became aestheticized one could posit that the earliest widespread distribution of what we could call somewhat artistic Western rope bondage images occurred in the late 1940's and early 1950's in the United States. This came about through the efforts of two distinct and interesting individuals. The first was Irving Klaw (1920-1966) who was based in New York City and the second was the more peripatetic and much more mysterious John Willie, real name Alexander Scott Coutts, (1902-1962) who worked his way from England to Australia to Canada and then to New York, NY and finally to Hollywood, California.

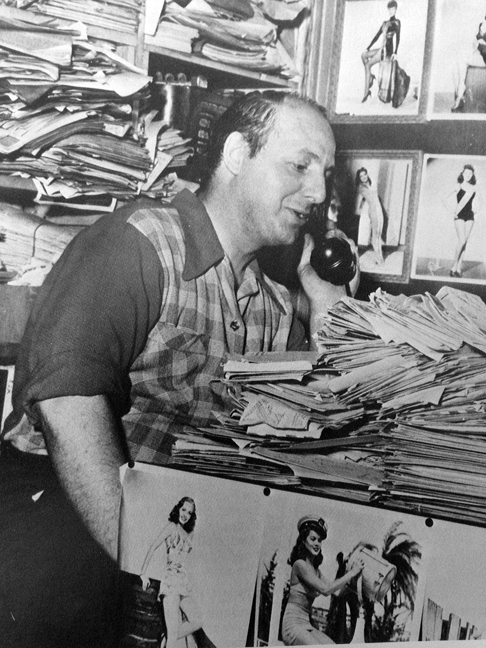

Irving Klaw in his NYC movie stills shop, circa the 1950's.

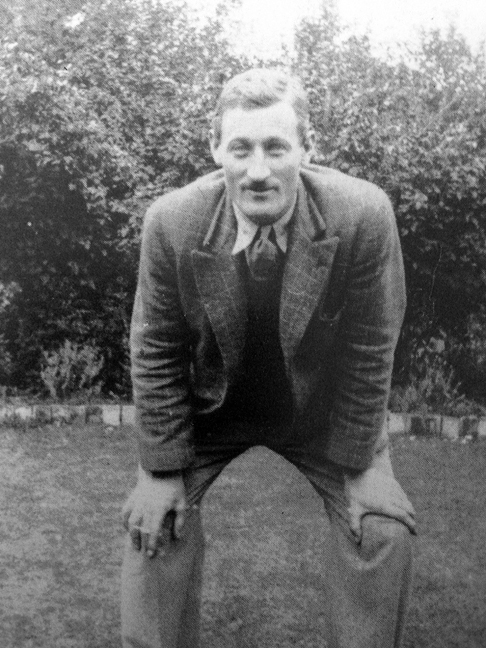

John Willie in a family photo taken in England, circa 1939.

Irving Klaw was what in the old days would have been called a “peddler of smut.” He ran a business in Manhattan that sold movie stills but moonlighted on the side doing very innocent looking pornography (at least to today’s eyes). Along the way he found that many of his customers preferred the movie stills he sold that depicted actors and, mostly, actresses tied up and so decided to turn out his own product to fill an increasing demand.

Klaw’s creative partner in all this was his sister Paula who really did most of the tying and photography in order to turn out the many sets of bondage photographs that her brother then shipped to his mail order customers or sold to his store’s many walk-ins and regulars.

The bondage in these efforts was generally very straightforward and typical of what you would expect of the Western approach, although it did have its creative moments. In this the Klaws were mightily assisted by the good fortune of employing one of the great early “fetish models,” the legendary Betty Page. Her remarkable figure, wholesome good looks and willing and winning smile that seemed to say, “Hey, this is all just fun,” went a long way toward putting Irving Klaw and his Nutrix Co. on the map and eventually in the cross hairs of US Government censorship. Still, one can’t really say of the Klaw material that it was especially creative rope work, except in rare instances.

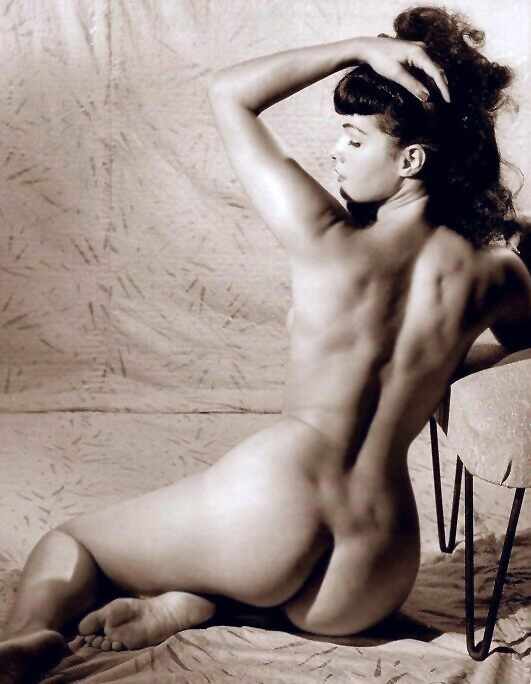

The legendary glamour and bondage model Betty Page, circa the 1950's.

Betty Page in bondage, produced by Irving Klaw, circa the 1950's.

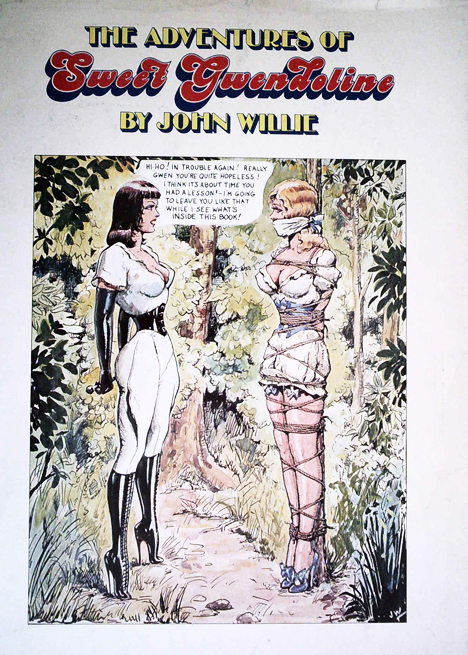

On the other hand, John Willie has come down to us as a figure of far more creative substance. Not only was he a brilliant illustrator and cartoonist who created the now legendary “The Adventures of Sweet Gwendoline” cartoon series (which he self published for many years) but he also published the landmark fetish magazine “Bizarre” and was a very good writer, photographer and, more importantly for this article, a very creative rope handler. According to people who knew him, he liked women, was safety conscious and always wanted his models to enjoy their work of posing in bondage for his photos which Willie then used as studies for his illustrations (much in the manner of the great early 20th century Japanese artist Itoh Seiyu).

Cover of John Willie's "The Adventures of Sweet Gwendoline." New York: Belier Press (original edition), 1974.

In fact, it would not be too much to say that Willie’s work was the model for much of the creative rope and photography that went into the early “bondage magazines” published in the United States in the 1970’s and 1980’s, to say nothing of his being an icon to many modern practitioners, such as the very skillful John Savage and all of those folks at the now defunct Harmony magazine company, who all credit Willie as one of their chief sources of inspiration. The question is: who inspired John Willie and where did he get his skills?

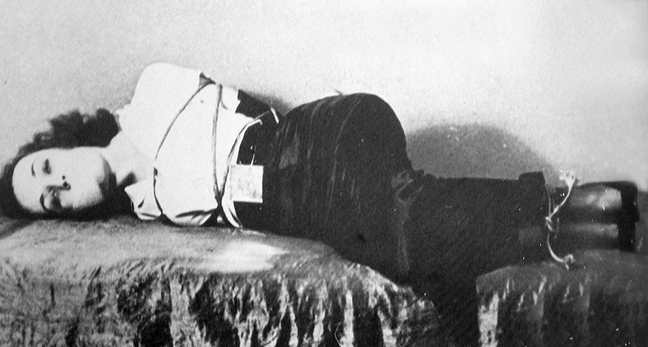

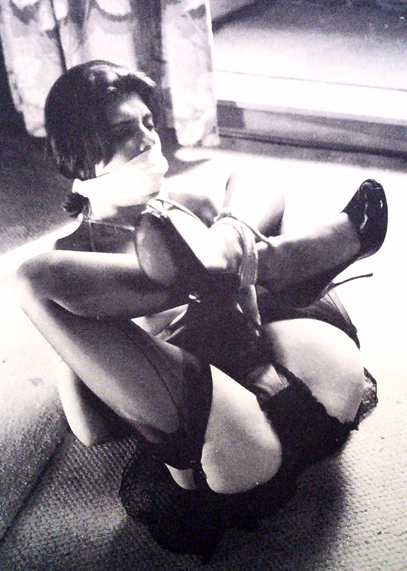

If one is fortunate enough to own several of the very nice books that have been published over the years that reproduce John Willie’s photography and art (see the end of this article for a short list) it quickly becomes apparent that early in his career John Willie, like Irving Klaw, did very basic, workmanlike ties that relied more on costume and fetishism then creative rope for their effect.

Early John Willie Western "bondage" photograph, circa the 1940's - 1950's.

The truth is, when one looks at the pages of "Bizarre," John Willie’s work and the best of Irving Klaw's images are virtually identical. It’s only when we begin to look at Willie's later bondage photography, which began to appear after he moved to Los Angeles in 1957, that we notice a distinct difference. The question is: what happened?

I stumbled upon what I believe to be the answer when I was writing about the various Japanese erotic and BDSM magazines that began to appear in good numbers during the postwar years. I found that as well as publishing their own Kinbaku art photography the Japanese also had a great interest in all sorts of fetish art and for this they began to import images from the West. These erotic illustrations were done by a number of Western artists such as Eneg, “Jim,” Stanton and they included the art John Willie did for his "Bizarre" magazine. Now, here’s where it gets interesting.

It seems that one of John Willie’s loyal subscribers and correspondents was a man who went by the nickname “Doc” and who was a military officer stationed after WW II in Okinawa. While there he took it upon himself to send those issues of such Japanese magazines as "Kitan Club" and "Uramado," etc. to John Willie whenever he saw one of the artist’s illustrations in their pages.

Willie got the magazines back in LA and began to notice not just his own credit but also the remarkably inventive tying that such early bakushi as Tsujimura Takashi and Minomura Kou (see “The Beauty of Kinbaku” for full biographies of these remarkable rope masters) were doing for their own publications in Japan. Astonishingly, this can be verified by Willie’s own business correspondence. Here, for example, is a somewhat florid excerpt from a brochure he sent out to customers from Hollywood which directly references the Japanese styles of tying he’d seen.

"The Japanese have a very simple way of teaching women obedience. The erring wife is tied securely, but not so tightly that it stops circulation, in a position which, though it may even allow a little movement, gradually becomes intolerable."

Perhaps even more convincing are the later Willie photos which happily have been published in several well done books and magazines over the years and clearly show John Willie copying Kinbaku ties he’d seen in the magazines he’d been sent.

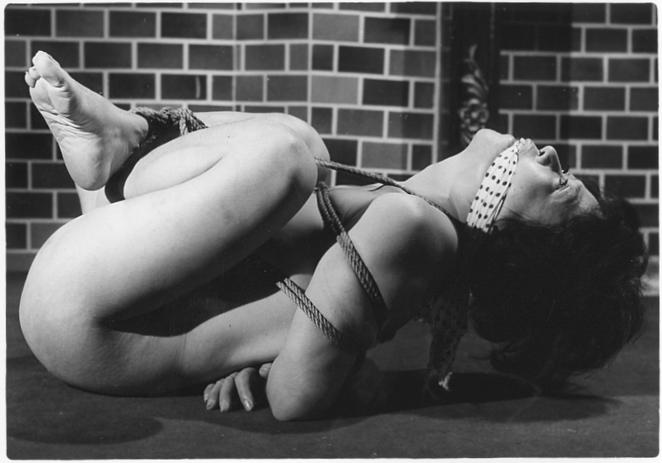

Here, for instance, is a photo from John Willie’s Hollywood years. This is clearly an ebi shibari, as any comparison to the original Japanese version of this tie makes clear.

John Willie's version of the Japanese ebi shibari, circa 1960, Hollywood, California.

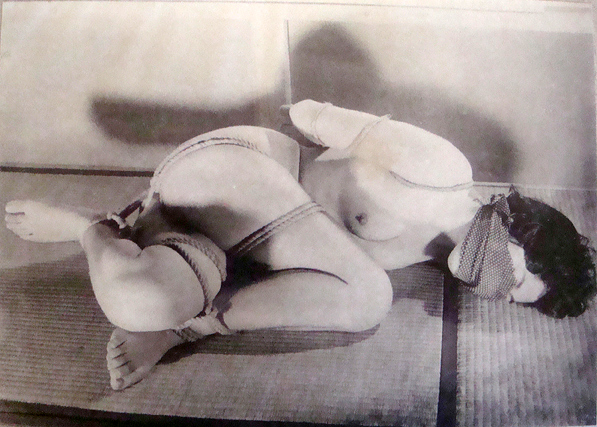

The same tie as it appeared in "Kitan Club" magazine, circa the 1950's.

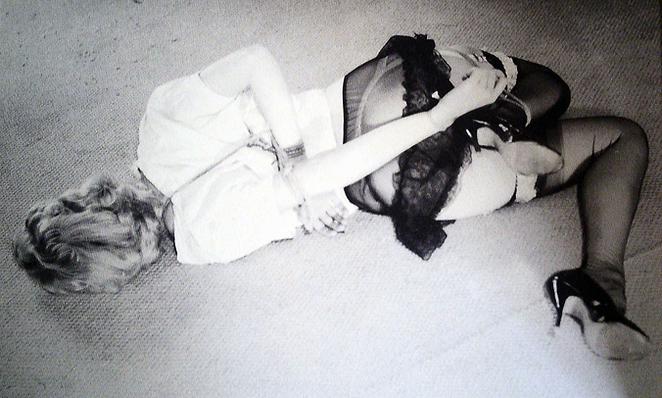

Here is another example that’s even more conclusive. This exotic and rarely seen Kinbaku tie was published by John Willie for his mail-order business in 1960. It’s quite unusual but is an almost exact copy of the distinctive “Green Caterpillar” shibari that was published in Minomura Kou’s landmark “Black Book” in 1953.

(Author’s note: please see chapters 1 and 2 of this series for more information on the most important Japanese Kinbaku art photography books ever published.)

John Willie's version of the "Green Caterpillar" tie, circa 1960, Hollywood, California.

The "Green Caterpillar" tie as it appeared in Minomura Kou's landmark "Black Book" in 1953.

These sorts of comparisons make it quite clear how John Willie advanced at least some of his knowledge and skill in doing creative, erotic rope. The irony in all this is that he hated the Japanese!

Willie fought for Australia in World War II and held, as many North Americans and Australians did at the time, a great dislike for their former enemy. Here is a quote from one of his letters as published in “The Works of John Willie.”

“Thanks a lot for the 2 packets of illustrations, Doc. My work seems to be quite popular in Japan, judging from the amount of it they reproduce, but I'm afraid I'm not flattered. The Australian army is not very fond of the Nips. In fact, I consider MacArthur’s rearming of the bastards a direct insult to every serviceman – US or Australian.” (Author’s note: General Douglas MacArthur was supreme Allied military commander in Japan after WWII and helped guide Japan’s postwar reconstruction.)

It’s unlikely that many of Willie’s US fans knew where his new and very creative style of tying was coming from. For instance, even so late a figure as John Savage (who was publishing in the 1970's and 1980's) referred to a tie that he clearly got from John Willie as the “Savage fold.” Of course, by any other name it’s still the ebi shibari that first appeared in Japan in the 1680’s! (Please see “The Beauty of Kinbaku” for more details.)

The John Savage "Fold."

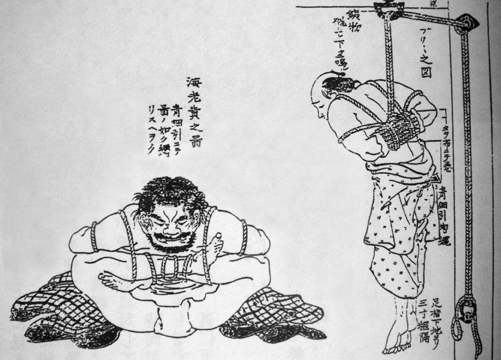

Illustration showing the classic ebi tie (left) and a suspension from a Japanese manual on Edo era (1603-1867) tortures.

It’s interesting to reflect on how much “Western bondage,” to say nothing of the publishing history of Western adult magazines after John Willie that featured bondage, are in debt to the centuries old Japanese art of Kinbaku and the unusual circumstances that finally brought it and the great John Willie together on our shores.

Please join us next time as we continue our exploration into the fascinating subject of “Kinbaku and Art!”

Note: Some of the most interesting and informative books and magazines on the history, art and photography of John Willie include:

1.) “The Adventures of Sweet Gwendoline” (Revised). New York: Belier Press Inc., 1999.

2.) “The Works of John Willie.” Patterson NJ: HCI Publishing, (no date).

3.) “Les Photographies de John Willie.” Paris: Futuropolis, 1985.

4.) “The Complete Reprint of John Willie’s Bizarre.” New York: Taschen, 1995.

5.) “The First John Willie Bondage Photo Book.” Van Nuys: London Enterprises Limited, 1978.

Links to Other Chapters of Kinbaku and Art